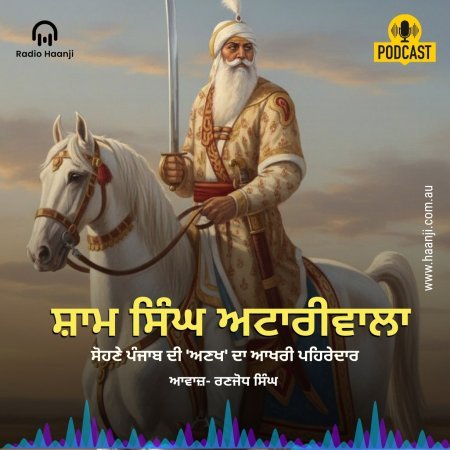

The Last Stand at Sobraon: Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala's Glory & Martyrdom

The epic story of Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala's martyrdom at Sobraon 1846. Betrayal, sacrifice & the fall of the Sikh Empire. Shared on Radio Haanji podcast by Ranjodh Singh.

The Last Stand at Sobraon

The Glory, Betrayal, and Martyrdom of Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala

Today, on Radio Haanji, Australia's premier Punjabi radio platform, host Ranjodh Singh shared the profound story of one of history's most stirring episodes of valor and sacrifice. This is the tale of Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala, the aging lion of the Khalsa who chose death over dishonor on the blood-soaked banks of the Sutlej River.

It is a story that begins in glory, descends into treachery, and culminates in a martyrdom so profound that even the British officers who witnessed it were moved to tears. It is the story of the Battle of Sobraon—fought on February 10, 1846—where the fate of the once-mighty Sikh Empire was sealed not by weakness of arms, but by the poison of betrayal from within.

The Golden Age: When the Khalsa Reached the Gates of Kabul

To understand the tragedy of Sobraon, we must first remember the glory that preceded it. There was a time, not so long before, when the Sikh Empire stood as one of the most formidable powers in all of Asia—a sovereign nation that struck fear into the hearts of Afghan warlords and commanded respect from the British themselves.

The Sher-e-Punjab: Maharaja Ranjit Singh

Born in 1780, Maharaja Ranjit Singh—the Lion of Punjab—transformed a fractured collection of Sikh Misls into a unified empire that stretched from the Khyber Pass in the west to Tibet in the east, from Kashmir in the north to the deserts of Sindh in the south.

His Khalsa Army was a marvel of the age: 100,000 disciplined soldiers, trained by European officers, equipped with modern artillery, and bound together by an unshakeable warrior spirit. This was no mere regional power—this was an empire that had conquered Multan, Kashmir, Peshawar, and Attock.

Ranjit Singh's vision was revolutionary for its time. His court welcomed Sikhs, Muslims, Hindus, and Europeans alike. Merit, not birth, determined advancement. The Golden Temple in Amritsar gleamed with newly applied gold, a symbol of Sikh prosperity and pride. Trade flourished. The arts bloomed. Punjabi literature reached new heights.

When British cartographers showed Maharaja Ranjit Singh a map of India, with British territories painted red, the one-eyed king studied it carefully and remarked with prophetic clarity: "Ek roz sab lal ho jaiga"—"One day it will all be red." He understood the British appetite for conquest. But during his lifetime, the red tide stopped at the Sutlej River. The British knew better than to challenge the Lion while he still drew breath.

The Spirit of Chardi Kala: At the heart of Sikh power was not merely military might, but an indomitable spirit known as Chardi Kala—eternal optimism and unwavering resolve in the face of adversity. This spirit had carried the Sikhs through centuries of persecution, had transformed a religious community into a martial race, and had created an empire where once there had been only scattered warriors.

The Darkness Descends: Treachery After the Lion's Death

???? June 27, 1839When Maharaja Ranjit Singh died in 1839, he left behind an empire at the height of its power—but no capable heir to guide it. What followed was a period so dark, so filled with treachery and bloodshed, that it seemed as if the very soul of the Khalsa had been poisoned.

The Serpents in the Court: The Dogra Brothers

Chief among the traitors were the Dogra brothers—Gulab Singh and his family—who had risen to positions of immense power during Ranjit Singh's reign. But loyalty, it seemed, had died with the Lion.

Within a decade, four successors to Ranjit Singh's throne were assassinated. Maharaja Kharak Singh, his son Nau Nihal Singh, Maharaja Sher Singh, and the young Prince Peshaura Singh—all fell to the daggers of conspiracy. The royal family was being systematically eliminated.

By 1843, the throne had passed to Maharaja Duleep Singh, a child of merely five years. Real power rested with his mother, Maharani Jindan Kaur—the youngest and most spirited of Ranjit Singh's widows. She fought desperately to hold the crumbling empire together, but the rot had set in too deep.

The state treasury—once filled with the wealth of conquests, including the famed Koh-i-Noor diamond—was being systematically looted. The vizier Hira Singh Dogra attempted to flee Lahore with cartloads of gold and jewels, only to be killed by troops loyal to Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala. But for every thief caught, two more emerged from the shadows.

The British Calculations: Lord Ellenborough's Sutlej Campaign

Across the Sutlej, British eyes watched the chaos with calculating interest. Lord Ellenborough, the Governor-General, saw in Sikh disunity the perfect opportunity. The British began massing troops along the border—ostensibly for "defensive purposes"—but their intent was clear to all who had eyes to see.

The British strategy was diabolic in its simplicity: they would not need to defeat the Khalsa Army—they would engineer its own destruction from within. And they found willing instruments in Tej Singh and Lal Singh, two generals who placed personal ambition above national loyalty.

The Treacherous Generals: Tej Singh and Lal Singh had secured their positions through palace intrigue rather than battlefield valor. Lal Singh was rumored to be Maharani Jindan's lover, while Tej Singh had purchased his generalship with gold. Both men entered into secret correspondence with British Political Agent Major Henry Lawrence, agreeing to betray their own army in exchange for British favor after the inevitable defeat.

The Appeal to the Aging Lion

???? Early February 1846After the Khalsa Army suffered defeats at Mudki, Ferozeshah, and Aliwal—battles lost not through lack of courage but through deliberate sabotage by Tej Singh and Lal Singh—Maharani Jindan Kaur made a desperate decision.

She sent ten horsemen riding through the night to the village of Attari, bearing an urgent message for Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala, the grizzled veteran who had served Maharaja Ranjit Singh with distinction in the conquests of Multan, Kashmir, Peshawar, and the frontier provinces.

The Contrast of Joy and Duty

When the Queen's messengers arrived at Attari, they found the aging general in the midst of joyous celebration. His son was getting married, and the household was alive with music, laughter, and the traditional ceremonies that mark such happy occasions in Punjabi culture.

The old warrior read the Maharani's letter by lamplight. She pleaded with him to save the Khalsa Army, which was now entrenched at Sobraon, desperately awaiting reinforcement and leadership that would not betray them.

Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala was no fool. He had watched the political machinations in Lahore with disgust. He had opposed the war with the British from the start, knowing it was engineered by traitors. He was now in his fifties, an age when most men seek rest, not war. He could have declined. He could have stayed with his family, celebrated his son's wedding, and lived out his days in honored retirement.

But he was a soldier of the Khalsa. And when his Queen called, he answered.

Before departing Attari, Sardar Sham Singh called his wife to him. With the calm acceptance of a man who has made peace with his fate, he told her: "Arrange my funeral rites. I shall not return from this battle."

He dressed in white—the color of purity, the color worn by those who have already surrendered themselves to death. Then he mounted his beloved horse, Shah Kabutar (King Pigeon), and rode toward Sobraon.

The Climax: February 10, 1846—The Battle of Sobraon

???? Dawn, February 10, 1846The Khalsa Army had established formidable entrenchments on the left bank of the Sutlej River near the village of Sobraon. The defensive works stretched two and a half miles, with batteries placed six feet high, protected by deep trenches. Behind these fortifications stood 20,000 to 25,000 men and seventy guns.

A single pontoon bridge connected this position to the west bank—the only route of retreat should things go wrong. It was this bridge that would become the instrument of ultimate betrayal.

When Sardar Sham Singh arrived at the camp, the soldiers' spirits lifted. Here was a leader they could trust—a general who had fought alongside the great Maharaja himself, who knew victory not through treachery but through courage and tactical genius. The immortal Akali Nihangs, led by Akali Hanuman Singh, rallied to his banner.

The British Assault

Across the river, British Commander-in-Chief Sir Hugh Gough and Governor-General Sir Henry Hardinge prepared their forces. The British had 20,000 infantry, 1,200 cavalry, and a heavy artillery train that had been brought up specifically for this assault.

The battle began in heavy fog. As it lifted, 35 British heavy guns and howitzers opened fire. The Sikh cannons replied in kind. For two hours, the bombardment continued without much effect on either side. The Sikh defenses, though weakened by poor placement orchestrated by the treacherous generals, still held firm.

Then Gough received news that his ammunition was running low. His alleged response has become legendary: "Thank God! Then I'll be at them with the bayonet!" He ordered the general assault.

The Breach and the Fury

British divisions under Harry Smith and Walter Gilbert made feint attacks on the Sikh left, while Major General Robert Henry Dick's division launched the main assault on the Sikh right flank—the weakest point, where loose sand made high earthworks impossible.

It is widely believed that Lal Singh had provided this critical intelligence to the British Political Agent Henry Lawrence. The betrayal ran that deep.

Dick's division gained footholds within the Sikh lines, but the Khalsa soldiers fought with such ferocity that the British were driven back. In the savage hand-to-hand combat, some frenzied Sikh warriors even attacked British wounded lying in the ditches—an act born of desperation and rage that enraged the British troops.

General Dick himself was killed in the assault. But the British, Gurkhas, and Bengal regiments renewed their attacks with fresh fury. They broke through at several points along the entrenchment. The battle had reached its crisis point.

The Ultimate Betrayal: The Bridge of Death

⚔️ Midday, February 10, 1846As the British penetrated deeper into the Sikh positions, Tej Singh—who commanded the reserves on the west bank—made his move. He fled across the pontoon bridge to supposed safety.

The Bridge is Cut

What happened next remains one of history's most debated acts of treachery. Multiple accounts claim that Tej Singh either:

- Deliberately weakened the pontoon bridge by casting loose the central boat

- Ordered his own artillery on the west bank to fire on the bridge to prevent "British pursuit"

British accounts claim the bridge simply broke under the weight of retreating soldiers, weakened by three days of rain that had swollen the Sutlej.

Whatever the truth, the result was the same: the bridge broke, trapping nearly 20,000 Khalsa soldiers on the east bank with the British closing in from all sides.

Major Carmichael Smyth later wrote: "Tej Singh ordered up eight or ten guns and had them pointed at the bridge as if ready to beat it to pieces or to oppose the passage of the defeated army."

The Sikh troops, basely betrayed by leaders who had sold them to the enemy, now faced annihilation.

The Martyrdom: A Warrior in White

And it was here, in this moment of ultimate betrayal, that Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala became immortal.

Dressed in his white robes—looking like a ghost among the smoke and carnage—the old general rallied his men for one final stand. When his beloved horse Shah Kabutar was shot from under him, he could have taken another mount and attempted to escape. Instead, he chose to fight on foot.

"We will not turn our backs!" he roared to his men. "Better to die as warriors than live as cowards!"

He led charge after charge against the British lines. His Akali Nihangs fought beside him, their blue robes and steel quoits flashing in the sun. They rushed forward sword in hand against muskets and cannons, choosing glorious death over shameful surrender.

Seven Bullets for Honor

Sardar Sham Singh fell where he stood, his body pierced by seven bullets. He died facing the enemy, his white robes stained red with his own blood and the blood of his foes. Around him lay his most loyal soldiers, who had chosen to die with their general rather than live without honor.

Not a single man in his detachment attempted to surrender. Not one.

Across the battlefield, others made the same terrible choice. Some rushed the British lines in suicidal charges. Others attempted to ford or swim the swollen Sutlej. British horse artillery lined the riverbank and fired into the drowning men. By the time the guns fell silent, between 8,000 and 10,000 Sikh soldiers lay dead.

— Captain Cunningham, British Officer at Sobraon

A Wife's Final Sacrifice

Back in Attari, when word of the battle reached Sardar Sham Singh's household, his wife knew without being told that he had kept his promise. Her husband would not return.

Without waiting for confirmation or news of how he had died, she made her own terrible choice. In keeping with the traditions of the time, she committed sati—immolating herself on a funeral pyre. She had been right in her conviction. The white-robed warrior would never come home.

The Aftermath: The Fall of an Empire

The Battle of Sobraon was the decisive engagement of the First Anglo-Sikh War. With the Khalsa Army shattered and the best of its generals dead or discredited, resistance collapsed. ???? February 20, 1846

Lord Hardinge entered Lahore in triumph. On March 9, he imposed a treaty on the seven-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh that reduced the once-mighty Sikh Empire to a British puppet state.

The terms were harsh: the Sikh state would pay a war indemnity of 1.5 million pounds, cede the Jullundur Doab to the British, and—most painfully—sell Kashmir to Gulab Singh Dogra for 750,000 pounds. The same Gulab Singh whose treachery had helped engineer the empire's downfall would now be rewarded with a kingdom of his own.

The legendary Koh-i-Noor diamond, once the pride of Maharaja Ranjit Singh's treasury, would eventually find its way to the British Crown, where it remains to this day.

Three years later, in the Second Anglo-Sikh War of 1848-49, even the pretense of Sikh independence would end. The Punjab was fully annexed by the British East India Company, and young Duleep Singh—last Maharaja of the Sikhs—would be separated from his mother and exiled to England.

The Legacy: When Honor Meant More Than Life

Today, on Radio Haanji's podcast, host Ranjodh Singh reminded listeners that the story of Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala is not merely a tale of military defeat—it is a testament to values that transcend the battlefield.

What the British Remembered

British regiments that fought at Sobraon celebrated "Sobraon Day" for years afterward, honoring the courage of the Sikhs they had fought against. The 10th (Lincolnshire) Regiment and 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment, which met in the captured trenches that had cost so many lives to take, formed a friendship that lasted generations. Their adjutants addressed each other as "My Dear Cousin" in official correspondence for over a century.

A fragment of the regimental color carried by Sergeant McCabe at Sobraon was enshrined in silver as "The Huntingdonshire Salt"—a revered relic of British military history.

But more than British respect, Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala earned something far greater: immortality in the hearts of the Punjabi people. Unlike many other battles of the Anglo-Sikh Wars, Sobraon and the role played by Sham Singh Attariwala is celebrated throughout Punjab and wider parts of India to this day.

Museums bear his name. Schools teach his story. February 10th is commemorated as Sobraon Day, when the descendants of those who fought remember the price of treachery and the value of honor.

— Lord Hardinge, who witnessed the battle

Reflections: The Bond Between a Warrior and His Motherland

As Ranjodh Singh concluded on today's Radio Haanji podcast, the true lesson of Sobraon is not about the fall of an empire—empires rise and fall with the turning of history's wheel. The true lesson is about the choices individuals make when faced with impossible odds.

Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala could have stayed home. He could have prioritized his family over his duty. He could have retreated when the bridge was cut. He could have surrendered when defeat became inevitable. At any of these moments, he could have chosen survival.

But he was a warrior of the Khalsa. And for such men, there are values more precious than life itself: honor, duty, loyalty to one's people, and the refusal to compromise one's principles even in the face of certain death.

The Eternal Spirit

When the fog cleared on the morning of February 11, 1846, the battlefield of Sobraon was silent. But the spirit that had animated Sardar Sham Singh and his warriors lived on. It lived in the Second Anglo-Sikh War. It lived in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. It lived in every Punjabi who fought for India's independence.

And it lives today, whenever we remember that some bonds—between a warrior and his motherland, between a soldier and his sacred duty—cannot be broken by defeat, cannot be dimmed by time, and cannot be erased by the victors' accounts of history.

The aging lion of Attari rode to Sobraon knowing he would not return. He put on white robes knowing they would soon be stained red. He fought on foot when his horse was killed because retreat was never an option. He took seven bullets because surrender was inconceivable.

And in dying as he chose to die—facing the enemy, surrounded by his loyal warriors, refusing quarter even when all was lost—Sardar Sham Singh Attariwala achieved something far more lasting than victory on a battlefield. He became immortal.

Continue the Journey Through Sikh History

This story is one of many preserved and shared by Radio Haanji, Australia's leading Punjabi radio platform dedicated to keeping our history, culture, and heritage alive for future generations.

Host Ranjodh Singh brings these epic tales to life through meticulous research and passionate storytelling, connecting the Punjabi diaspora across Melbourne, Sydney, and beyond to their glorious past.

What's Your Reaction?