911 History: How the World's Emergency Number Was Born in 1968 - Punjabi Podcast - Radio Haanji

Host:-

Ranjodh Singh

Ranjodh Singh

On February 16, 1968, a red phone rang in Haleyville, Alabama and changed emergency services forever. Discover the full history of 911, 999, and 112 worldwide.

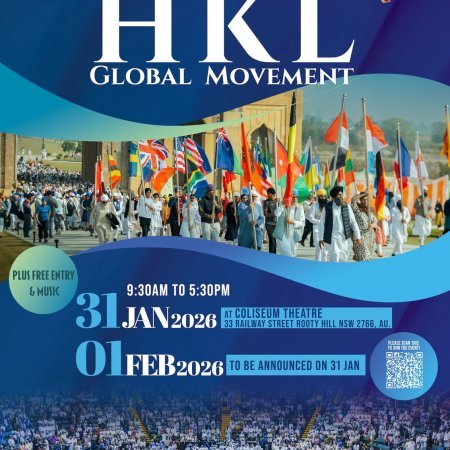

History of 911 and Triple Zero 000: How Emergency Numbers Changed the World

At exactly 2:00 p.m. on February 16, 1968, a bright red telephone rang at the Haleyville police station in a tiny Alabama town most Americans had never heard of. A U.S. Congressman walked across the room, lifted the receiver, and said one word: "Hello." That single word—picked up on the other end by Alabama's House Speaker dialing from the mayor's office down the hall—launched the most consequential three digits in modern history. The number was 9-1-1. And nothing about emergency services would ever be the same again.

Every year on February 16, the world quietly marks the anniversary of that first 911 call. It's not a holiday anyone celebrates with fireworks or parades, yet the ripple effect of what happened in Haleyville, Alabama, touches every person alive today. Whether you've dialed 911 yourself in a moment of panic or simply lived with the comfort of knowing you could, your life has been shaped by a small-town telephone company's audacious decision to beat AT&T to history.

This fascinating history was recently explored in depth on Haanji Melbourne, a popular show on Radio Haanji 1674 AM—Australia's number 1 Indian and Punjabi radio station. Host Ranjodh Singh took listeners through the remarkable stories behind emergency numbers worldwide, from the red telephone in Alabama to Australia's own Triple Zero, connecting these historical moments to the immigrant experience of learning new countries' emergency systems. The discussion reminded the Indian and Punjabi community in Melbourne and Sydney that understanding emergency services isn't just practical knowledge—it's part of becoming truly at home in a new land.

????️ Featured on Radio Haanji 1674 AM: This history of emergency numbers was discussed on Haanji Melbourne, hosted by Ranjodh Singh. Radio Haanji is Australia's premier Indian and Punjabi radio station, broadcasting 24/7 to connect communities across Melbourne, Sydney, and beyond. Tune in to 1674 AM or stream via the Radio Haanji mobile app for educational content, news, and the best Punjabi podcast programming in Australia.

Before the Digits: A World Without Emergency Numbers

To truly understand why February 16, 1968, matters, you have to first understand what the world looked like without a unified emergency number—and it was terrifying in its chaos.

Imagine your house is on fire at midnight. You need to call for help immediately. But which number do you dial? Your local fire department? That's one number. The police? That's a different number entirely—and it might vary depending on which precinct covered your block. An ambulance? Yet another number, provided you even knew it. And all of these numbers were multi-digit local numbers that changed from city to city, from neighborhood to neighborhood.

People routinely died because they wasted precious minutes desperately searching phone directories—sometimes in smoke-filled rooms, sometimes while bleeding, sometimes while watching someone they loved lose consciousness. The system was so broken that even calling the operator (by dialing "0") wasn't a reliable solution; operators were often undertrained to route emergency calls quickly and accurately.

"If you're having a heart attack, that's not what you want—to be figuring out which number to dial." — NPR's account of Haleyville's historic achievement

The problem wasn't a lack of telephones. By the 1960s, millions of Americans had phones in their homes. The problem was a catastrophic failure of standardization. Emergency response existed in silos—disconnected, locally governed, impossible for a panicked person to navigate efficiently.

Britain Gets There First: The 999 Story (1937)

The idea of a single emergency number wasn't born in America. That credit belongs to the United Kingdom, and the story of how it happened is itself a product of tragedy.

In November 1935, a fire broke out on Wimpole Street in London. Five women died. A subsequent investigation revealed something infuriating: several neighbors had tried to call the fire brigade but couldn't get through because the local telephone exchange was overwhelmed. People were trying to reach help, but the system simply couldn't handle simultaneous emergency calls.

The British government acted. A special committee recommended creating a dedicated emergency number, and on June 30, 1937, London introduced 999—the world's very first dedicated emergency telephone number. The choice of 9 was deliberate: on rotary phones of the era, 9 was positioned at the far end of the dial, requiring maximum finger rotation, making it nearly impossible to dial accidentally. Callers were even given instructions on how to find the "9" in a darkened or smoke-filled room: locate the "0," then move your finger to the adjacent hole.

The very first 999 call came in the early hours of the next morning, at 4:20 a.m., when the wife of John Stanley Beard dialed to report a burglar lurking outside her home at 33 Elsworthy Road, Hampstead, London. Police were dispatched. The age of the emergency number had begun.

Did you know? The UK's 999 number was introduced just two years before World War II. During the war, American military personnel stationed in England encountered the system—and many would carry the memory of that efficiency back home, helping to eventually inspire America's push for its own emergency number.

Triple Zero: Australia's 000 — Built for the Outback

While Britain and America were solving their emergency number challenges, Australia faced a uniquely different problem. It wasn't just about cities struggling to route calls—it was about a continent where a person might be hundreds of kilometres from the nearest town, dialing a telephone on a crackling outback line in pitch darkness, with no hope of help unless the system worked perfectly under the worst possible conditions.

The solution was characteristically Australian: practical, robust, and designed for the harshest environment on Earth. The number chosen was 000—Triple Zero.

Before Triple Zero: A Patchwork of Chaos

Prior to 1961, Australia did not have a national number for emergency services; the police, fire, and ambulance services possessed many phone numbers, one for each local unit. Just as in America and Britain before their respective reforms, Australians faced the terrifying prospect of searching through directories in moments of crisis. In remote areas, this wasn't just inconvenient—it could be a death sentence.

1961: The Postmaster-General Acts

In 1961, the Postmaster-General's Department (PMG)—the government body that controlled Australia's telephone infrastructure before Telstra existed—introduced Triple Zero across major Australian cities. During the 1960s, coverage was extended nationwide. It was a phased rollout rather than a single dramatic moment like Haleyville, but no less important.

The choice of 000 was driven by two brilliant pieces of engineering logic specific to the Australian context:

First: The darkness problem. The number 000 was chosen because zero was easy to dial in darkness — the digit zero sat next to the finger stop on most Australian rotary dial telephones. In a country where a farmer might need to dial emergency services by feel alone — power out, no torch, a snake bite or a bushfire closing in — finding the right digit without seeing the dial was not a trivial concern. Zero was the anchor point of the rotary phone. Find the stop with your finger, back up one hole: that's zero. Dial it three times. Done.

Second: The outback signal problem. Zero, being the longest rotary pulse, created a distinctive signal that could stand out from the interference often present on rural lines. In remote outback Queensland and the Northern Territory, telephone lines ran for extraordinary distances and picked up electrical interference, static, and signal degradation. Each digit on a rotary phone sent a series of electrical pulses — "1" sent one pulse, "9" sent nine pulses, and "0" sent ten pulses, the maximum. Three zeros sent thirty pulses in a very specific pattern that was nearly impossible to generate accidentally from line noise, ensuring that emergency calls weren't triggered by static.

A uniquely Australian engineering decision: Technically, 000 suited the dialling system for the most remote automatic exchanges, particularly outback Queensland. In the most remote communities, two 0s had to be used to reach a main centre — so dialling 0+0+0 would, at minimum, connect to an operator. The number wasn't just a hotline — it was built into the very architecture of how remote Australia connected to the outside world.

Why America's 911 Was Rejected for Australia

It's worth noting that 911 was previously considered as a potential emergency number for Australia, but existing numbering arrangements made this unfeasible — homes and businesses had already been assigned telephone numbers beginning with 911. Australia thus arrived at 000 independently, through its own geographic and technical reasoning, rather than simply borrowing the American model.

How Triple Zero Works Today

Today, 000 or Triple Zero is the primary national emergency telephone number in Australia and the Australian External Territories. Triple Zero calls are initially answered by a Telstra Emergency Access Service Point, then transferred to the requested state and territory emergency services organisations.

When you dial 000, a Telstra operator answers first and asks a single, critical question: "Emergency — police, fire, or ambulance?" Your call is then immediately transferred to the relevant service in your state or territory. The entire handoff happens in seconds, designed to minimize the time between your call and the dispatch of help.

Importantly, Triple Zero calls can be made without charge, whether the mobile service is active, suspended, disconnected, or out of credit for a prepaid service. In emergencies, financial barriers simply do not exist. Even if the mobile account is inactive, disconnected, blocked, or suspended — or if there is no SIM card in the phone — you can still call 000.

The Modern Challenge: Location in the Outback

Australia's greatest ongoing challenge with Triple Zero is the same one that haunted its original design: the tyranny of distance. Unlike calling 000 from a Sydney apartment — where your address appears instantly on a dispatcher's screen — calling from a hiking trail in the Kimberley, a station in outback Western Australia, or a beach on the Cape York Peninsula presents a fundamentally different problem. Your GPS coordinates may be the only way to find you.

In response, Australia developed the Emergency+ app, which uses a phone's GPS to display the caller's precise location, allowing them to read coordinates aloud to the operator. Advanced Mobile Location (AML) technology — fully rolled out nationally by August 25, 2021 — uses smartphone GPS, Wi-Fi positioning, and hybrid methods to transmit sub-10-metre accurate coordinates automatically during 000 calls, a transformative upgrade from earlier cell-tower triangulation that was sometimes inaccurate by more than a kilometre.

For those with speech or hearing impairments, 106 is the Australian national textphone/TTY emergency telephone number, ensuring that Triple Zero services are accessible regardless of a caller's communication ability.

Critical reminder for anyone in Australia: If you're calling 000 from a mobile phone in a remote area and aren't sure of your address, open the Emergency+ app before you need it. It could save your life — or someone else's. And remember: when called on a mobile or satellite phone, the international standard number 112 will be redirected to Triple Zero. So whether you dial 000 or 112, help is on the way.

As Ranjodh Singh noted on Haanji Melbourne, one of the most important things for new immigrants to learn is their country's emergency number. For those coming from India (where emergency numbers include 100 for police, 101 for fire, and 102 for ambulance), adapting to Australia's single Triple Zero system can be lifesaving knowledge. Radio Haanji's commitment to educating the Indian and Punjabi community on practical Australian systems—from emergency services to healthcare to education—makes it an invaluable resource for both new arrivals and long-established residents.

America Wakes Up: The Long Road to 911

The United States watched Britain's success with interest but moved with the characteristic American combination of enthusiasm and bureaucratic delay. The journey from concept to reality took over three decades and required, among other things, a murdered woman whose story would shake the national conscience.

The Firefighters Who Started It All (1957)

The first formal push for an American emergency number came in 1957, when the National Association of Fire Chiefs recommended creating a single national number for reporting fires. Their argument was straightforward: firefighters were dying because response times were too slow, and response times were slow because the public couldn't efficiently summon help. A single, memorable number, they argued, would save lives.

The recommendation landed on desks in Washington but went nowhere for a decade. There were jurisdictional arguments, infrastructure concerns, and the thorny question of who would pay for it all. The telephone industry, dominated by AT&T (known colloquially as "Ma Bell"), was the only entity with the infrastructure to make it happen nationally—and AT&T had its own timeline.

Kitty Genovese and the Urgency of a Crisis (1964)

Sometimes, tragedy accelerates what bureaucracy delays. On March 13, 1964, Kitty Genovese—a 28-year-old bar manager in Queens, New York—was stabbed to death outside her apartment building in two separate attacks spanning 30 minutes. The New York Times reported (somewhat inaccurately, as later investigations revealed) that 38 neighbors had witnessed the attacks without calling police.

The story caused a national firestorm. Psychologists coined the "bystander effect" in response to it. But beneath the social commentary was a more practical issue: even those who did want to call police faced a confusing tangle of precinct numbers. The lack of a simple, universal emergency number was suddenly not just inconvenient—it was framed as a threat to public safety at a societal level.

Congress began paying closer attention. The case for a national emergency number gained political urgency it hadn't had before.

The Presidential Commission Acts (1967)

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice formally recommended creating a single nationwide number for reporting emergencies. The FCC was tasked with making it happen and immediately began negotiations with AT&T, which held a near-monopoly on American telephone service.

On January 12, 1968, AT&T made its historic announcement: the company would designate 911 as the national emergency number across its Bell System networks. The Wall Street Journal broke the story, and suddenly every independent telephone company in America—there were roughly 2,000 of them, serving 20% of the country's telephones—realized they'd been left out of the conversation entirely.

The Sneaky Alabama Telephone Company That Beat AT&T to History

Bob Gallagher was not the kind of man who liked being left out. The president of the Alabama Telephone Company (ATC), an independent carrier serving 27,000 subscribers across 27 exchanges in northwestern Alabama, read AT&T's announcement in the Wall Street Journal and felt something between indignation and inspiration.

AT&T hadn't consulted ATC or any other independent company. They'd simply announced their plan and assumed the rest of the industry would follow. Gallagher had other ideas. His father had been a firefighter back in Huntington, West Virginia—Gallagher understood viscerally why emergency response times mattered. He wasn't going to let "Ma Bell" take sole credit for this moment in history.

"I told him I think we can do a 911 system and beat AT&T out," Gallagher recalled. "And he said go get 'em. And off we went."

Gallagher evaluated all 27 of ATC's telephone exchanges and selected Haleyville—a small town of under 5,000 people in Winston County, northwestern Alabama—as the best candidate. The company was already updating Haleyville's infrastructure, making technical installation straightforward. His team worked after hours to design and implement the 911 switching system in under a week.

He then called in political favors. Alabama House Speaker Rankin Fite was asked to make the first call. U.S. Congressman Tom Bevill was recruited to receive it at the Haleyville police station, where a special bright red telephone—provided by ATC, designated solely for 911—had been installed.

The Moment History Was Made: 2:00 p.m., February 16, 1968

The scene at Haleyville on February 16, 1968, had the feel of a small-town ceremony that knew it was doing something big. Mayor James H. Whitt waited alongside Rankin Fite in the city hall office. At the police station, Tom Bevill stood with Gallagher and Bull Connor—the infamous former Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner who was now president of the Alabama Public Service Commission—watching the red telephone on the desk.

At exactly 2:00 p.m., Rankin Fite picked up a phone in the mayor's office and dialed three digits: 9-1-1. The call passed through ATC's newly configured switching equipment. Across the building, the bright red telephone rang.

Congressman Tom Bevill lifted the receiver. He said one word.

"Hello."

It was not, as the Smithsonian Institution noted years later, as poetic as Samuel Morse's "What hath God wrought?" But it was the beginning of something equally transformative. The headline in the February 18 issue of the Daily Northwest Alabamian announced Haleyville's place in history. The town would later add the 911 achievement to its city welcome signs.

"Immediately afterward, we had coffee and donuts," Bevill recalled decades later, with characteristic southern understatement. The 25-year anniversary interview showed he was still amused by the quiet morning that had become a historic milestone.

AT&T, determined not to be completely scooped, made its own first 911 call in Huntington, Indiana, on March 1, 1968—exactly two weeks after Haleyville. But history had already been written in Alabama. Today, the original red telephone sits on display in Haleyville City Hall, surrounded by framed newspaper clippings and proclamations—a shrine to three digits that saved millions of lives.

Why 9-1-1? The Logic Behind the Numbers

The choice of 911 wasn't arbitrary. Every digit was deliberate, the result of engineering constraints, switching system requirements, and human psychology working together.

It had to be short. Three digits maximum—easy to remember under panic, fast to dial, impossible to confuse with standard phone numbers.

It couldn't already exist. Unlike 411 (directory assistance) or 611 (service), 911 had never been authorized as an area code, office code, or service code anywhere in the United States. It was genuinely unique.

The rotary phone factor. In 1968, most American homes still used rotary dial telephones. The number 9 was positioned at the far end of the dial, requiring the longest rotation—meaning it was the hardest digit to accidentally dial. More importantly, the sequence 9-1-1 could be dialed very quickly: a long rotation for the 9, then two fast short rotations for the 1s. The number 999 (which America briefly considered, as Britain used it) would have required three long rotations, making it significantly slower.

The middle 1 was a signal. Telephone switching equipment of the era recognized numbers beginning with a "1" in the middle position as special service codes (alongside 411, 611, and 811). This meant 911 would be recognized by the telephone system as a non-standard call requiring special routing—exactly what emergency calls needed.

⚡ Key Facts About 911

911 calls answered annually in the United States alone

public safety telecommunicators employed at US call centers

calls answered per day across America

of 911 calls in the US are made from mobile phones (as of 2018)

it took for three-quarters of Americans to gain 911 access after 1968

Emergency Numbers Around the World

While 911 dominates North American consciousness, the world's emergency numbers tell a rich story of independent problem-solving, colonial legacies, and technological cooperation.

The European Union's adoption of 112 in 1991 is a story of political will overcoming national inertia. The EU mandated that all member states implement 112 as a standard emergency number, working alongside existing national numbers. Today, dialing 112 anywhere in the EU connects you to emergency services—a remarkable achievement of cross-border standardization that has saved countless lives among travelers who wouldn't know the local number.

Australia's 000 has an interesting origin: it was chosen partly because 0 was the fastest digit to dial on Australian rotary phones, and partly to create a code that was extremely difficult to accidentally dial (three consecutive zeros required deliberate, precise action). New Zealand's 111 was adopted in 1955 and implemented starting 1958, but was chosen because of the unique layout of New Zealand rotary phones where "1" occupied the position equivalent to "9" on British dials.

The Evolution of 911: From Basic to Enhanced to Next Generation

The 1968 Haleyville call used what is now called "Basic 911"—a simple voice connection between caller and dispatcher. When you called in 1968, the operator knew only what you told them: your name, location, and nature of the emergency. If you panicked and couldn't speak, help might never come.

Enhanced 911: The Address Revolution

The game-changing upgrade came with Enhanced 911 (E911), rolled out through the 1980s and 1990s. For the first time, dispatchers could see your phone number and address displayed on their screen the moment your call connected. This was transformative: callers who were injured, confused, or too frightened to speak could still receive help because dispatchers knew where to send it.

In 1999, the Wireless Communications and Public Safety Act officially declared 911 the universal emergency number for the United States. The same year, the FCC began requiring phone companies to provide location data for mobile 911 calls—a recognition that 80% of future calls would come from cell phones, not landlines.

Text-to-911: Helping Those Who Cannot Speak

One of the most important modern developments was Text-to-911, first tested in Iowa in 2009. The ability to text emergency services transforms 911 access for the deaf and hard-of-hearing community, for victims of domestic violence who cannot safely speak, and for anyone in a situation where making a voice call would escalate danger.

Next Generation 911: The Future Is Digital

The current frontier is Next Generation 911 (NG911)—a complete migration of 911 infrastructure from aging analog telephone networks to modern digital IP-based systems. NG911 will enable video calls to 911, real-time text communication, the ability to share photos and videos of emergencies with dispatchers, and dramatically improved location accuracy for mobile callers.

The September 11, 2001 attacks—where 911 systems were overwhelmed by the volume of calls—accelerated federal investment in modernization. The government's commitment to strengthening emergency infrastructure became a national security priority.

The Human Side: Who Answers the Call

Behind every 911 call is a human being sitting in a dispatch center, trained to remain calm while absorbing other people's worst moments. For decades, 911 dispatchers were classified as administrative staff—a designation that denied them the mental health resources, compensation, and recognition given to police, fire, and paramedics who responded in person.

The reality is that dispatchers are often the first voice a desperate person hears. They talk jumpers off ledges, talk panicked parents through infant CPR, stay on the line with domestic violence victims until police arrive, and process information from callers who are injured, incoherent, or dying. They hear sounds that they cannot unsee. The psychological toll is immense.

In 2019, Texas led the way by passing legislation to include dispatchers in the legal definition of "emergency responder"—granting them access to mental health services and benefits previously unavailable. Other states have followed, though progress remains uneven. The movement to properly recognize 911 dispatchers as first responders is one of the most important ongoing stories in emergency services today.

"Immediately afterward, we had coffee and donuts." — U.S. Congressman Tom Bevill, reflecting on the first 911 call in 1968, with remarkable Alabama understatement

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did Australia choose 000 as its emergency number?

Which was the world's first emergency number?

Why was 911 chosen as the emergency number?

What is the emergency number in Europe?

????️ Discover More Educational Content on Radio Haanji

Tune in to Haanji Melbourne with host Ranjodh Singh on Radio Haanji 1674 AM for more insightful discussions on history, culture, and practical knowledge for Australia's Indian and Punjabi community. Available 24/7 on 1674 AM in Melbourne and Sydney, or stream online via the Radio Haanji mobile app and all major podcast platforms including Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and YouTube.

The Weight of Three Digits

The next time you see the numbers 9-1-1 on a keypad, or tap out 0-0-0 on an Australian phone, take a moment to consider what they represent: over 85 years of human ingenuity, political will, tragedy-driven urgency, and brilliant engineering combining to create the most important phone numbers ever dialed. From a fire in 1930s London that killed five women, to a murdered woman in Queens whose story galvanized Congress, to an Australian postmaster-general engineering a number that could be dialed by a farmer in complete darkness hundreds of kilometres from the nearest town — the story of emergency numbers is ultimately a story about what happens when people decide that the status quo is simply not good enough. On February 16, every year, that red phone in Haleyville's City Hall stands as a reminder, as does every Triple Zero call answered across Australia: sometimes, three digits are all that stand between crisis and salvation.

What's Your Reaction?